noVNC and QEMU RFB keyboard extension

Web-based KVM management tools such as Ovirt help users to create and manage virtual machines (VMs) easily, even from mobile devices. Such tools rely on remote desktop-sharing technology such as Virtual Network Computing (VNC), and those that use VNC require a web-based VNC client such as noVNC.

The initial goal of VNC was to enable a physical PC to be accessible remotely. Because virtualization wasn’t a VNC concern, the interpretation and manipulation of keystrokes when VNC is used with VMs requires special handling. Web technologies bring additional challenges: Web apps must work around differences in browser support or else limit use to a few selected browsers. And web apps’ access to PC hardware is limited by the browser API, whereas desktop apps have more direct access.

This article aims to help JavaScript developers understand and address the challenges involved in making a web-based VNC client (or any other web-based hardware emulator facing the same issues) capable of responding accurately to keystrokes generated from multiple keyboard layouts. I start by explaining how desktop operating systems handle keyboard signals. Then, you learn how RFB (the protocol that VNC uses) sends keystrokes from the VNC client to VNC server, the problems that this process involves in virtualization scenarios, and how the QEMU community solved those problems for desktop VNC clients. Then, I show how a relatively Then, I show how a relatively new browser API can be used to implement the QEMU solution for web-based VNC clients.

Before proceeding, I highly recommend to check out this article from Daniel Berrange. His article gave the technical foundation of everything that is going to be discussed here.

How the OS processes keystrokes

A keyboard is a hardware device that sends a signal for each pressed or released key. These signals, called scancodes, consist of one or more bytes that uniquely identify the physical key press or release.

IBM set the first scancode standard with the IBM XT. Most manufacturers followed the XT standard to ensure device compatibility with IBM hardware. However, the scancode isn’t a good keyboard representation for applications to use, because different keyboard types can use different scancodes. USB keyboards, for example, follow a different scancode standard from the XT standard.

Keycodes

To enable applications to deal with any type of keyboard, the OS translates the scancodes to keyboard-independent keycodes. Pressing Q in a PS2 keyboard, for example, yields the same keycode as pressing Q in a USB keyboard. Thanks to the translation from scancode to keycode — the first task of the keyboard driver— applications don’t need to deal with all known keyboard types.

The translation between scancode and keycode is reversible. Any keycode can be translated back to the exact hardware scancode that generated it. For example, pressing the key labeled Q on a standard US 102-key keyboard isn’t interpreted as Q was pressed but as the key located in the second column of the third row was pressed.

Key symbols (keysyms)

Working with keycodes still isn’t ideal for applications, because the same physical key can represent different symbols depending on the keyboard layout. In a French keyboard, for example, the key located in the second column of the third row is A, not Q. Most applications — text editors, for example — want to know that the user pressed Q, not where the pressed key is located in the layout.

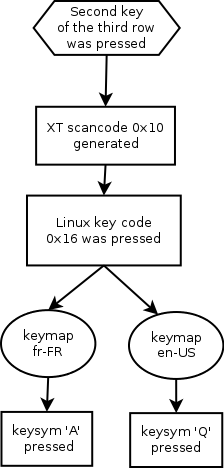

Key symbol (keysym) is the symbol that’s generated from one or more key presses/releases after the keyboard map (keymap) is considered. The translation from keycode to keysym is the last transformation the OS makes, delivering the exact keysym to the application. The figure below illustrates the translation sequence that I just described for an XT-compatible keyboard sending a key press to a Linux-based system from either a US or a French keyboard layout.

Unlike the scancode-to-keycode translation, the translation from keycode to keysym isn’t reversible, for two reasons. First, the translation involves knowing the keymap used to generate the keysym, and this information isn’t available in all scenarios. Second, there’s no way of knowing which key combination was used to create the keysym. For example, the keysym for A can be produced by either pressing Shift + a or by pressing a with Caps Lock on. This ambiguity is the source of the problems that QEMU experienced with RFB.

The RFB protocol, QEMU/KVM virtualization, and VNC

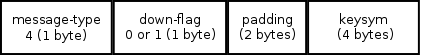

RFB (Remote Framebuffer) is the protocol that VNC uses for remote access to GUIs. Among the several types of RFB client-to-server messages defined in the protocol and its extensions, our interest here is the KeyEvent message, which is sent from the RFB client to the server when a key is pressed or released:

- message-type specifies the type of the message. KeyEvent messages are type 4.

- down-flag indicates the state of the key. If the key was pressed, the value is 1; if released, the value is 0.

- padding is a zero-filled two-byte field.

- keysym is the keysym of the pressed or released key.

When receiving a KeyEvent message, the RFB server replicates the keysym in the remote desktop as either pressed or released, depending on the value of the down-flag . Use of the keysym value in this message was the root cause of a design problem that early QEMU versions had with the VNC clients/servers for virtualization.

QEMU, being a hardware emulator, doesn’t merely receive and display the keystrokes; it emulates them as if someone were pressing keys on a real keyboard in the VM. As a result, on receiving a RFB KeyEvent message, QEMU tries to convert the sent key to the XT scancode that would generate it. However, the KeyEvent message sends the keysym. QEMU was faced with the challenge of how to retrieve the actual XT scancode from a pressed or released key, based on the keysym.

The QEMU project first tried introducing a keymap option to tell QEMU which keymap was used in the VNC client that generated the keysym (the -k option). With this information, QEMU could try to translate from keysym back to scancode; if no keymap was specified, it would use the default US layout. This approach wasn’t adequate for solving QEMU problems with non-US keyboards. QEMU needed to be able to support any keyboard layout used by the VNC client (layouts for 100+ languages).

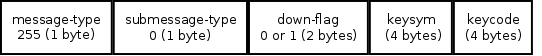

The solution using -k doesn’t scale. An alternative was presented in an official extension to the RFB protocol, adding a new KeyEvent message with an extra ‘keycode’ field:

- message-type specifies the type of the message. The extended QEMU KeyEvent messages are type 255.

- submessage-type has a one-byte default value if zero.

- down-flag indicates the state of the key. If the key was pressed, the value is 1; if released, the value is 0.

- keysym is the keysym of the pressed or released key.

- keycode is the keycode that generated the keysym.

With the extra keycode information, QEMU can reverse the keycode to the scancode and emulate it. This capability also makes the VNC server unaware of which keymap is being used by the VNC client. Provided the keymap of the client is the same as the keymap configured in the guest OS (the OS running in the VM), the keyboard works as expected.

Web technologies and keystroke handling

The differences in keyboard event handling between desktop apps and web apps add a layer of complexity to implementing a web-based VNC client fully. That layer is the browser. Desktop apps can access the underlying hardware more directly, whereas web apps are limited by browser support.

Basics of keystroke handling in the browser

Browsers provide three keyboard events to web applications:

- keydown : A key is pressed down.

- keyup : A key is released.

- keypressed : A character key is pressed.

The keydown and keyup events are similar to the keyboard events that the OS deals with. The keypressed event occurs only when a keysym is generated. Special keys such as Shift or Alt don’t generate a keypressed event. For a web app to get the generated characters reliably, it must rely on the keypressed event.

Each event has at least these three properties:

- The keyCode property refers to the key pressed without modifiers such as Shift or Alt. When the a key is pressed, the keyCode is the same even when the keysym generated is A. Many websites and web tutorials misleadingly call this property the scancode of the key.

- The charCode property is the ASCII code of the keysym generated by the key event, if any.

- the ‘which’ property returns the same value as keyCode most of the time, giving the Unicode value of the pressed key.

At the beginning of 2016, a new KeyboardEvent property called code was included in the Chrome browser stable version 48. (Firefox had introduced this property earlier, and later it became available in Opera too.) The Mozilla Developer Network describes this property as follows:

KeyboardEvent.code holds a string that identifies the physical key being pressed. The value is not affected by the current keyboard layout or modifier state, so a particular key will always return the same value.

This new attribute can properly represent what a keycode represents in RFB semantics, enabling a Javascript implementation of QEMU RFB extension in noVNC.

The extended QEMU KeyEvent extension is well established and implemented in several desktop VNC clients. Now that the KeyboardEvent.code property makes it possible to recover the physical key being pressed, VNC web clients have no reason not to follow suit and implement the extension too. The solution that I implemented for the noVNC project can be used by any web-based VNC client.

Ignoring the keypressed events

I chose to ignore keypressed events in the solution. These events are only triggered when a readable character (a keysym) is produced by one or more keypressed events. When detecting a connection from a client that has support for the QEMU VNC extension, the QEMU VNC server will (most of the time, as I’ll discuss later) simply ignore the message’s keysym field, relying only on the keycode field to emulate the XT scancode in the VM.

Code implementation

The full working implementation that I designed is available on GitHub in the noVNC project. Here’s some interesting details about it:

How to convert KeyboardEvent.code to xt_scancode

The KeyboardEvent.code gives the physical position of the key, but not in an format that can be use directly in the RFB message. Here’s an example of the possible values for this property:

'Esc' key: xt_scancode 0x0001 keyboardevent.code = "Escape"

Spacebar: xt_scancode 0x0039 keyboardevent.code = "Space"

'F1' key: xt_scancode 0x003B keyboardevent.code = "F1"

My implementation uses the table provided in this Mozilla Developer Network article on KeyboardEvent.code to create a hash that translates a KeyboardEvent.code value to the corresponding xt_scancode — for example:

XT_scancode["Escape"] = 0x0001;

XT_scancode["Space"] = 0x0039;

XT_scancode["F1"] = 0x003B;

Creating the QEMU RFB KeyEvent message

Considering buff as a byte array of size 12:

buff[offset] = 255; // msg-type

buff[offset + 1] = 0; // sub msg-type

buff[offset + 2] = (down >> 8);

buff[offset + 3] = down;

buff[offset + 4] = (keysym >> 24);

buff[offset + 5] = (keysym >> 16);

buff[offset + 6] = (keysym >> 8);

buff[offset + 7] = keysym;

var RFBkeycode = getRFBkeycode(keycode)

buff[offset + 8] = (RFBkeycode >> 24);

buff[offset + 9] = (RFBkeycode >> 16);

buff[offset + 10] = (RFBkeycode >> 8);

buff[offset + 11] = RFBkeycode;

It’s no accident that the structure of the data resembles Figure 3. In this code, keycode is the xt_scancode translated from the keyboardevent.code value, and keysym is a zero field (in most cases).

The getRFBkeycode() function translates the XT_scancode to the format that the QEMU VNC extension defines:

function getRFBkeycode(xt_scancode) {

var upperByte = (keycode >> 8);

var lowerByte = (keycode & 0x00ff);

if (upperByte === 0xe0 && lowerByte < 0x7f) {

lowerByte = lowerByte | 0x80;

return lowerByte;

}

return xt_scancode

}

Handling NumLock

In the first version of my implementation of the solution — which completely ignored the keysym field of the QEMU KeyEvent message — one curious behavior was happening: When any multiuse numeric keypad key — 0, 1,2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, or the decimal separator (period in en_US layouts) — was pressed, even with the NumLock state ON on both the VM and the client, the QEMU VNC server would:

- Change the VM NumLock state to OFF (if it was ON )

- Press the key

For example, pressing the Numpad 8 key with NumLock state ON on both client and VM would turn the NumLock state OFF in the VM and then execute the arrow-up key. Pressing the Numpad 8 key with NumLock state OFF works as expected.

This problem can be solved by reliably syncing the NumLock states of both client and VM. But it’s impossible for the remote QEMU VNC server to know about the NumLock state of the client keyboard. The server can see when the NumLock key is pressed/released, but it has no information about the current NumLock state, because that information isn’t passed by the QEMU VNC KeyEvent message.

After extensive testing with desktop VNC clients, I realized that the keysym was being sent in those circumstances. Although the keycode doesn’t change based on NumLock state, the keysym is is affected. The conclusion is that the QEMU VNC server uses the keysym field to guess the NumLock state of the client and act accordingly to try to sync the VM state. In the implementation where the keysym was being sent as zero, the server interpreted this as “NumLock state of the client is OFF ,” forcing the client NumLock state to OFF and then sending the keycode pressed.

Because sending no keysym defaults the NumLock state to OFF , the solution is to send the keysym only when the NumLock state is ON.

Sending the keysym for the Numpad

The keyboard event that produces the keysym is the keypressed event, which my solution ignores. So how can the keysym be supplied to the QEMU KeyEvent message?

Fortunately, the keypressed event isn’t necessary for determining the keysym. The numeric keypad is standard across all layouts (otherwise, without the keymap, the QEMU VNC server wouldn’t be able to guess the NumLock state). So, the keysym values for the Numpad keys can be predetermined.

That leaves the question of how — without using the keypress event — the case where Numpad 7 is used as Home can be differentiated from using it as the number 7. My implementation uses the KeyboardEvent.keyCode property, which is set at the keydown event, to make this differentiation, as illustrated in the following code excerpts.

The following function receives a keyboard event evt and compares the KeyboardEvent.code value to the values that belong to the numeric pad:

function isNumPadMultiKey(evt) {

var numPadCodes = ["Numpad0", "Numpad1", "Numpad2",

"Numpad3", "Numpad4", "Numpad5", "Numpad6",

"Numpad7", "Numpad8", "Numpad9", "NumpadDecimal"];

return (numPadCodes.indexOf(evt.code) !== -1);

}

I use the preceding function to see if for a specified keyboard event any special processing is required.

The following function receives a keyboard event evt and compares its keyboardevent.keyCode property to a predefined set of values called numLockOnKeyCodes:

function getNumPadKeySym(evt) {

var numLockOnKeySyms = {

"Numpad0": 0xffb0, "Numpad1": 0xffb1, "Numpad2": 0xffb2,

"Numpad3": 0xffb3, "Numpad4": 0xffb4, "Numpad5": 0xffb5,

"Numpad6": 0xffb6, "Numpad7": 0xffb7, "Numpad8": 0xffb8,

"Numpad9": 0xffb9, "NumpadDecimal": 0xffac

};

var numLockOnKeyCodes = [96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102,

103, 104, 105, 108, 110];

if (numLockOnKeyCodes.indexOf(evt.keyCode) !== -1) {

return numLockOnKeySyms[evt.code];

}

return 0;

}

The numLockOnKeyCodes values correspond to the numeric keypad key 0 to 9 plus the decimal separator in the NumLock ON state. If evt.keyCode is one of those values, the function returns the equivalent keysym given by numLockOnKeySyms ; otherwise, it returns zero.

Here’s how these functions are called inside the code:

result.code = evt.code;

result.keysym = 0;

if (isNumPadMultiKey(evt)) {

result.keysym = getNumPadKeySym(evt);

}

In this code, result is the object that’s passed along for processing. This way the solution ensures that the NumLock keys are being taken care of correctly.

AltGR and Windows

Another anomaly emerged when I tested my first implementation in all supporting browsers (Chrome, Firefox and Opera) running on Windows 10: The AltGR modifier key didn’t work as expected on Linux VMs.

By debugging the code, I discovered that the AltGR key was being sent to the QEMU VNC server with two KeyEvent messages instead of one. The first message was a left Ctrl key; the second message was a right Alt key — the same effect you’d expect from someone pressing left Ctrl and immediate after right Alt. When the client is run in a Linux PC, the AltGR key is sent as right Alt.

The reason for this behavior is historical. Long story short: Older US keyboards didn’t have the AltGR key, and Windows started emulating it using left Ctrl + right Alt. This solution is fine for keyboards that don’t have the AltGR key but can be misleading when keyboards with AltGR are used.

One solution would be to document this behavior and force users to remove this default mapping. Another is the solution that I chose — to handle the behavior in noVNC. The code includes special handling for the combination left Ctrl followed by right Alt:

if (state.length > 0 && state[state.length-1].code == 'ControlLeft') {

if (evt.code !== 'AltRight') {

next({code: 'ControlLeft', type: 'keydown', keysym: 0});

} else {

state.pop();

}

}

(...)

if (evt.code !== 'ControlLeft') {

next(evt);

}

(...)

This code tells noVNC: In a keydown event, if the KeyboardEvent.code is equal to ControlLeft , do not forward the event right away. Wait for the second keydown event and verify if its code is equal to AltRight , which means that browser received a left Ctrl + right Alt combination — which can mean that the AltGR key was pressed in a Windows browser. In this case, discard the left Ctrl press and forward only the right Alt, which is the default behavior in Linux. This handling enables the AltGR key to work as expected even in Windows browsers.

The drawback of this approach is that the left Ctrl + right Alt combination isn’t forwarded even if it was legitimately pressed by the user. I consider this an acceptable downside because left Ctrl + right Alt isn’t a usual key combination (left Ctrl + left Alt and right Ctrl + right Alt are much easier to type). The usability impact is minimal, and the user is relieved from dealing with reconfiguring keymaps on Windows.